Afghanistan is synonymous with conflict. While most analyses have focused on the human actors—the intractable web of foreign fighters, international terrorist organizations and fleeing refugees—the key to understanding conflict is the environment. Given the severity of violence, it may seem odd to use the environment as a lens to understand an active conflict zone. But in fact, it is through these complex social-environmental relationships that one can begin to unravel the regional drivers of vulnerability.

The natural environment is often disregarded as an actor in most conflict settings, a reality that has led to the destruction of countless landscapes. As documented in the Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo and Colombia, the collapse of formal environmental protections, combined with an influx of nefarious actors, has devastated many of the world’s biodiversity hotspots. Perhaps unique to Afghanistan, however, is the intensity of the second order effects of land degradation, and the way these hazards affect vulnerable populations on the ground.

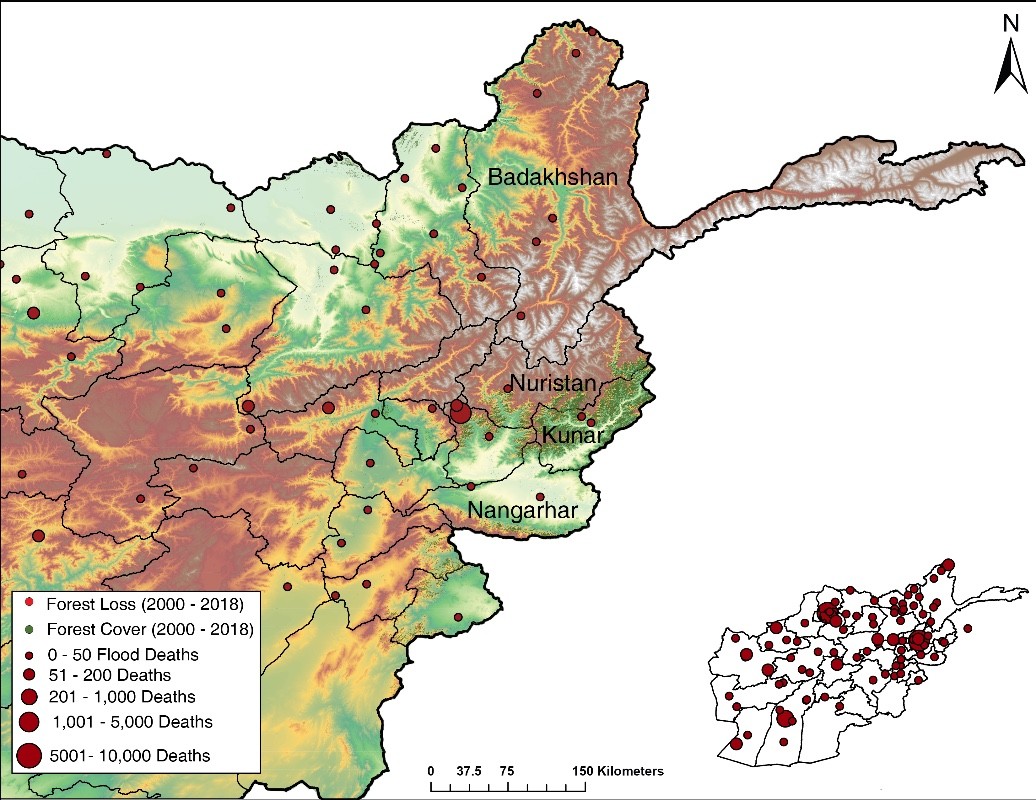

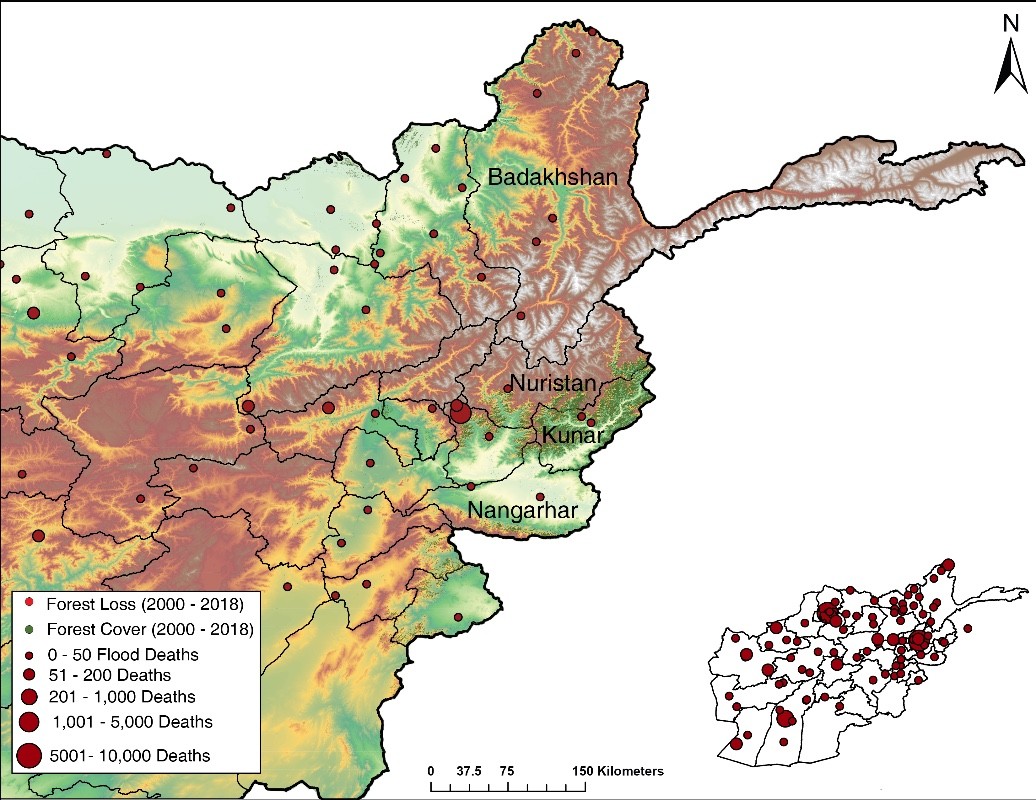

Over the four decades since the Soviet invasion in 1979, the ecosystems of Afghanistan—particularly the once lush mountainous Hindu Kush region—have been dramatically transformed. From 1977 to 2002, 51 percent of forest cover in the northern provinces of Nangarhar, Kunar, Badakhshan and Nuristan was lost to deforestation, a trend that has only continued in the past two decades. Illicit Taliban and Islamic State timber networks further degraded the region.

The combined loss of forested terrain and shift in rangeland use during the conflict created a cycle of pervasive desertification and erosion. Precipitation that once fell and dispersed through river networks and into the permeable landscape is now running off with alarming frequency. Without tree roots to hold soil, and sufficient soil absorption due to prolonged periods of drought, debris flows and flash floods have become increasingly common, affecting hundreds of thousands of people and exacerbating the suffering of groups already facing extreme insecurity.

During the wet spring months, especially during El Niño events where there is a higher likelihood of above normal precipitation in northwest Afghanistan, rainfall has begun to behave in more unpredictable ways. Historic flooding swept through parts of the Hindu Kush region in 2010 and again in 2013. Due in part to the influence of this season’s El Niño as well as the protracted drought in 2018, flooding hit the region once again this March, leaving hundreds dead and tens of thousands displaced.

Afghan people in the region have been largely unable to access disaster aid sent in response to this disaster, a consequence of the Taliban’s resurgence and slew of killings of aid workers by militant groups in recent years. Given the complexity of the regional power struggle, and the continued degradation of the Hindu Kush landscape, it is unlikely that the natural hazard risks will subside. Without significant work to abate the culpable timber trade, reversal of decades of landscape degradation, and establishment an accessible early warning system, the Afghan people are sure to continue to face these risks alone.